Managing Health and Mental Well being of Urban Poor to build climate resilient cities

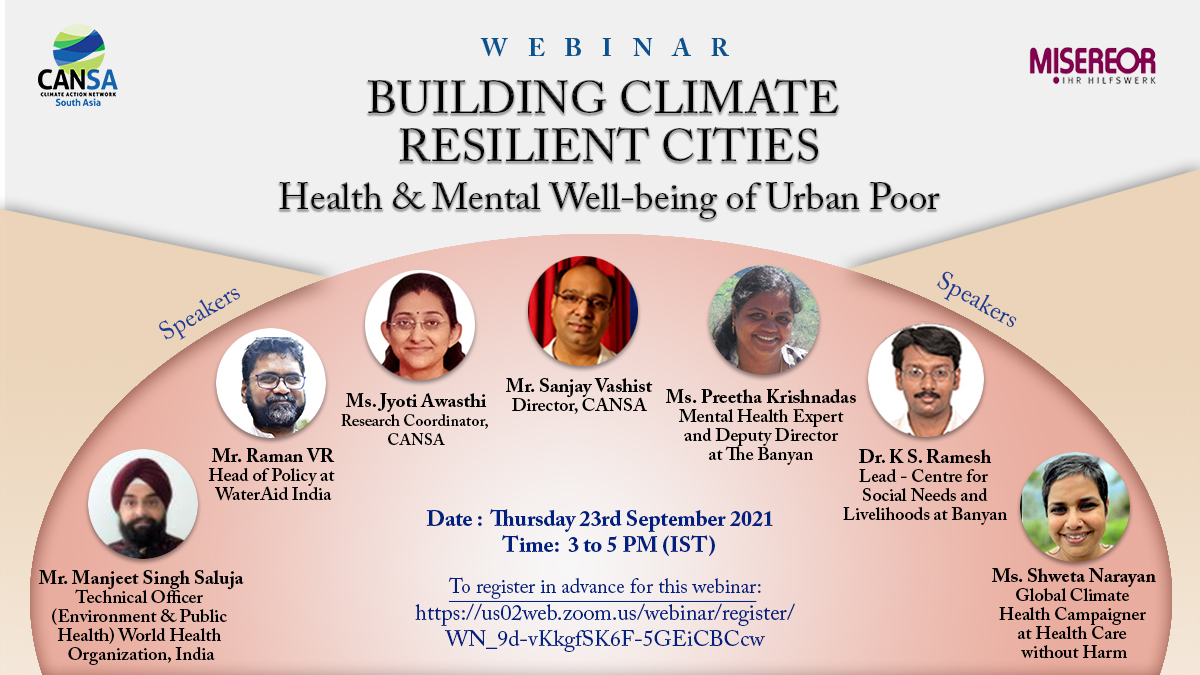

In the webinar series organised by CANSA on ‘Building Climate Resilient Cities’, the fourth and last webinar on Health & Mental well-being of Urban Poor, was conducted on 23 September 2021.

The urban poor remain a highly neglected community by#UrbanPlanners, and when smart or #ClimateResilientCities are planned, this segment of the population is completely ignored. All stresses have an impact on health and mental well-being, and has an even greater impact on the lives of urban poor in a changing climatic situation, given the lack of resources in which they lead their daily lives. Waterlogging, overflow of drains and scarcity of fresh drinking water and contaminated water – all these lead to the spread of several communicable diseases, especially impacting the urban poor who live in miserable conditions in the absence of adequate infrastructure. Living on roadsides, in shanties, this community bear the brunt of long exposure to #AirPollution, that include respiratory problems. Another concern is the impact on #MentalHealth due to long persisting stress and immediate trauma in a post climate crisis situation. We all realise the fact that mental health and well-being is the most neglected or least understood issue in the society and when it comes to raising it as one compounding problem faced by poor communities, it hardly finds any takers both in the governance and polity.

With the objective of understanding these issues, Climate Action Network South Asia (CANSA) chose to delve into this subject and understand it from experts so that the network and associated civil society can articulate the problems and seek solutions from the government and polluters both.

The context of the webinar was set by Jyoti Awasthi, Research Coordinator, CANSA, whereas Sanjay Vashist, Director, CANSA, made the final closing remarks. Among the speakers were those who have worked extensively with #UrbanPoor communities, and on health issues, particularly mental health are Raman VR, Head of Policy, WaterAid India, and Manjeet Singh Saluja, Technical Officer at World Health Organization-India; Dr K.S. Ramesh, Lead at Centre for Social Needs and Livelihood at Banyan, Preetha Krishnadas, Deputy Director at The Banyan, and Shweta Narayan, Global Climate Health Campaigner at #HealthCare without Harm.

Jyoti Awasthi said that while we consider the impacts of climate change on those living on river banks, coasts or hills or agriculture-dependent communities, we completely ignore a huge segment of urban people who live in poverty, i.e., the city. They can’t afford to buy a safe place in the city, so they live on the roadsides or along the drains, where they get impacted during a flash flood or waterlogging. This causes health problems and loss of livelihood. This problem is a systemic one, not an individual one. Climate change creates even more misery in the lives of urban poor. Therefore, it is very important for climate communities to come closer to them and see where the overlaps are, and how these issues can be addressed. Their mental health problems and the trauma needs to be understood more closely, and in the context of climate change especially.

Raman V.R. started by addressing a question how the health and well-being of urban poor is being affected. Urban poor or homeless people in slums and informal settlements and migrant workers in shared spaces, all face many struggles for their basic living infrastructure and fulfilling the primary needs. They faced income loss during the pandemic, and several challenges in terms of health and poor nutrition. A large number of advanced tertiary and super-speciality facilities do not serve the health needs of poor. There are water supply and sanitation problems.

During lockdowns, most urban slums were buying drinking water at higher prices and basic health systems were shifted to handling the pandemic, causing a toll to the health services for urban poor. Sanitation systems were not functional, many lost jobs, and food did not reach them in many cases. Media support was sadly lacking and the poor migrant labour were portrayed as villains of the story. In fact, mental health concerns are yet to be understood. There is a need for sanitation workers to be formally included in the frontline for their well-being and nutrition initiatives should be taken. Mental health support programmes should be started.

Manjeet Singh Saluja spoke about the common issues for growing cities – health, access to basic services like housing, transportation, water and sanitation and also informal settlements and peri-urban slums, migration, unemployment, disease outbreaks, food safety. He explained about six useful information pathways:

- Current policies assessed with major impacts on air pollution and health are mapped along with key stakeholders in urban health and urban development sectors and civil society.

- Health professionals build competencies in assessing health and economic impact of policies and in advising other sectors on urban environmental health risks. Healthcare workers equipped to advise patients on protective measures.

- Tools for assessing health and economic benefits such as WHOs AIRQ+ , HEAT and One Health adapted and used locally.

- Alternative scenarios assessed based on policy options tested or considered locally to estimate potential health and economic impacts.

- Communications intensify demands for change – Urban leaders and champions engaged to communicate cost of inaction through locally developed communication strategy, intensifying demand for action. Healthcare workers advise patients and communities about prevention.

- Urban leaders action changes in air quality, climate and health indicators monitored and tracked. Health and economic arguments provide urban leaders with incentive to act, changes in air pollution and related policies monitored and tracked, using WHO Global Urban Ambient Air Pollution Database.

He concluded by saying there should be cooperation between different stakeholders and institutions not only to make the best use of finite resources but to capitalise on synergies and ensure policy coherence to achieve systematic change and ensuring access to the environmental determinants of health, such as clean air, water and sanitation, safe and nutritious food is an essential protection against all health risks.

K.S. Ramesh said that a state of well-being is one in which an individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community. During a disaster there is loss and damage, interruptions, injuries, displacement and separation, uncertainty in recovery and future. And the most vulnerable groups are children, elderly, differently abled, with chronic diseases, unemployed and homeless people. Impact on mental health has not been taken seriously where people go through depression, helplessness, sleeplessness, anxiety and people worry on safety, life, injury and basic access to shelter and facilities like toilets, food and clothes. These people go through substance abuse, illness, phobias, post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidal ideation and there is a high need to help these people overcome their mental health conditions.

Preetha Krishnadas a mental health expert at Banyan, emphasized that mental health is very vital and we have to look at different perspectives; there is need to talk about preventive aspects and whatever we can do from the intervention point of view. Access to treatment and access to shelter is very important. Mental health is crucial but it is not been given adequate importance in the health sector. If these people have access to get treated at the initial level, they will not become vulnerable. She concluded by saying that there should be mental health first-aid training and practice programmes, and mental health emergency services. Active advocacy with public like toll-free mental health helpline where incoming calls 24/7, should be active, and proactive efforts should be made for grief and bereavement needs. There must be life-skills training and certain policies made for people who are homeless during disaster situations.

Shweta Narayan stressed on the importance and danger of the issue of air pollution in context of human health. WHO’s latest guidelines are prioritising public health but Indian guidelines do not prioritise in public health; it does not protect public health. Children, pregnant women and elderly are most vulnerable to air pollution. The burden of air pollution in cities is disproportionately shouldered by the poor people, the urban poor. That is something we need to be conscious of, and be mindful of when designing either urban spaces or urban policies. By design the urban city is on that makes the poor more vulnerable. There is always a class and caste angle where the urban poor live and we call it environmental racism. There is an expectation from the urban poor to contribute towards smooth execution of whatever happens in the city. Even the odd-even cars on the road scheme in Delhi to combat vehicular pollution, was clearly targeted towards a certain class of people, forgetting the urban poor. A lot of our policies like air pollution mitigation policies or any other public policies does not pass the equity lens. That is the crux of the problem. She recommended that there should be public participation and equity and transparency in decision-making. What we need to consider going forward is not to make assumptions about air pollution and its impacts, but understand the problem in totality, from the lens of urban poor and also design solutions that benefit everybody.

Sanjay Vashist concluded the webinar by saying that mental health aspects have not been given enough importance at all, and it was only in school that this was touched upon and that too in a cursory manner, when we were told that a strong will can help fight any kind of threat. The webinars have been very insightful and CANSA will focus more on health aspects of climate change in the future.

Click here for Webinar recording, Passcode: gPwzV6r=

By Divyanshi Yadav, Communications Officer, CANSA

#AirPollution #ClimateResilientCities #HealthCare #MentalHeath #UrbanPlanners #UrbanPoor